This article is intended to provide an overview of certain rarely discussed copyright law issues in connection with construction designs and the buildings created on the basis of such designs.

Not only designers, architects and engineers but developers must also be aware that architectural works and their designs, and the designs of building complexes, engineering structures and urban landscapes (“architectural works”) are protected under Sections 1(2)k) and l) of Hungary’s Act LXXVI of 1999 on Copyrights (“Copyrights Act”). Therefore, the designer holds all copyrights from the moment that the work is created, i.e. the designer, as the copyright owner, is solely entitled to exploit and make adaptations to their design, or permit others to do so.

All this means is that if you want to create or recreate an architectural work embodied in a design, or to carry out alterations on an existing building, you will have to obtain a permission for the exploitation or alteration from the author of the design, or from their heirs for a period of 70 years after the designer’s death (“period of protection”) [Copyrights Act, Sections 9(1) and (6); Sections 18(1) and (2); Section 31].

If you plan to carry out alterations to a building, you should pay attention to these matters:

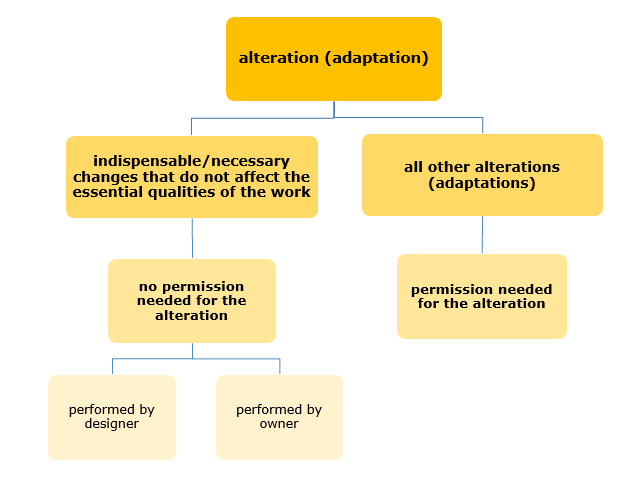

An author has the sole right to make adaptations to their own work, and to permit others to do so. Adaptation is the modification of a work, resulting in the creation of a derivative work (Copyrights Act, Section 29).

It should be noted in connection with adaptations that if the author has granted their permission to the exploitation of their work, they will be required to make changes to the work that is indispensable and clearly necessary for such exploitation but does not affect the essential qualities of the work (even if they have not specifically permitted adaptations). If the author does not comply with this obligation, the user may make the changes even without the author’s consent (Copyrights Act, Section 50). However, all other changes can qualify as a adaptations.

The addition of a new wing to an existing building can qualify as an adaption,[1] and so can any intervention in the spatial structure, or any change on the façade, of a building that results in the creation of a derivative work from the original work. Not only the modification of designs or drawings qualifies as an adaption but the alteration of an existing building also does. Alterations that qualify as adaptations are not limited to modifications that aim to change the appearance of a building; any redesign or alteration that enhances the building’s fitness for the purpose intended does too.[2]

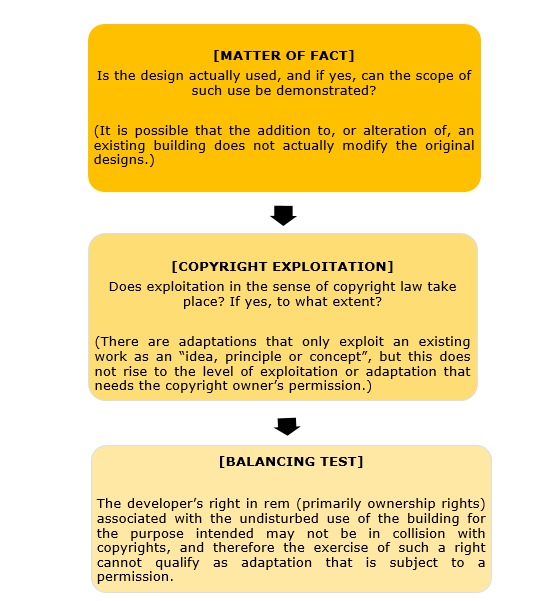

Before changing the use class of, carrying out alterations on, or extending or demolishing an existing architectural work, the following test that we have developed on the basis of the applicable case law and regulatory practices should be performed to determine whether what is planned will create any obligations for the developer or the owner.

The exploitation of a design as an original work of authorship can primarily take place in the form of incorporation to a new design. In a legal dispute, unauthorised use will have to be proven by the copyright owner. Therefore, one of the issues that will have to be proven is whether any part of a design has actually been used. The relevant case law[1] holds that a merely functional extension of a building, such as the addition of a new wing to an existing production facility, will not it itself mean that the designs of the existing building have been exploited, even though the extension resulted in the alteration of the entire building.

Therefore, the primary issue that has to be examined is whether the copyright-protected work is actually used in the alteration or addition that results in the modification of the building, because a change in the appearance of the building will not automatically mean that it does. For example, it does not amount to the use of a design if a new design takes some of the existing structural elements into account as a technical feature.[2]

Secondarily, it should be examined whether the use, if it actually takes place, qualifies as exploitation within the meaning of copyright law. The adoption of certain elements of a design will not necessarily amount to exploitation, because if the elements incorporated to the design do not rise to a level higher than an “idea, principle or concept”[3], exploitation in the copyright sense will not take place.[4]

If there is evidence that an existing design was used and it amounted to exploitation within the meaning of copyright law, it will still be questionable how a property owner’s theoretically unlimited right to dispose over their property relate to the designer’s copyright. An extreme interpretation might suggest that the owner will have to seek the designer’s approval for essentially any intervention that results in any change in the building. However, the relevant copyright case law is more nuanced.

Basically, a designer’s copyright in an architectural work will be considered to have been violated if an alteration is performed on the building without authorisation. Such a violation can be carried out by the property owner. The determination of whether the alteration of a building as a copyright-protected architectural work is performed with or without authorisation must be based on the premise that the copyright protection may not limit the owner’s right to use the building freely for the purpose intended. An owner has the right to alter or even demolish a building they own if their needs so dictate. While the rightful exercise of ownership rights may not result in the violation of a designer’s copyrights in the building, if the owner’s needs or requirements on the basis which the building was created no longer exist or have changed, the designer may not cite copyrights to prevent the original or any subsequent owner of the building from altering or demolishing the building, and may not question the lawfulness of the owner’s actions on the grounds that such actions represent a deviation from their design.[5]

In the third step noted above on the basis of the case law, the interests of the property owner and the designer must be balanced against each other to determine when the owner’s interests should prevail over those of the designer. The owner’s interests will typically prevail in cases where the addition is necessitated by practical reasons and the owner wants to carry out minor alterations that will increase the building’s functionality.

According to the opinion of the Copyright Experts Board[6], an owner can exercise their rights of ownership if the alteration or demolition of the architectural work is justified by a reasonable private or public need that may render the enforcement of copyrights wrongful. The assessment of whether this applies must carried out on a case-by-case basis. It should be also noted that there is another interpretation by the Copyright Experts Board which argues that the owner’s taste does not qualify as such a reasonable need.[7]

The right of adaptation is a stand-alone economic right, i.e. adaptation is special form of exploitation. [Copyrights Act, Sections 17.f) and 29] It is important to point out that a licence to use a work will only apply to adaptation if the parties expressly agree that it does [Copyrights Act, Section 47(1)], and therefore the developer or the owner of a building has a vested interest in agreeing with the designer in the relevant (design) contract that they will have the right to carry out adaptations on the design/building.

Agreement between the developer (owner) and the designer

Alterations of buildings often result in disputes that stem from a collision between copyrights (in the integrity of the work) and the owner’s right (in using and disposing over the work). In order to prevent such disputes, it is advisable for the developer to reach an agreement with the designer in the design contract, particularly with regard to the developer’s (owner’s) right of adaptation.

Therefore, it is advisable to agree in the design contract that

- the designer’s fee includes consideration for the exploitation of the design to the extent necessary for the relevant project;

- the designer’s fee includes consideration for the consent to the adaptation of the design; and

- the designer’s fee consists of two parts: i) consideration for the preparation of the design and (ii) royalty for the licence granted with regard to exploitation and adaptation.[8]

It should be emphasised that in the absence of an express agreement between the parties on adaptations, the original author’s permission will be needed for an adaptation until the end of the period of protection.

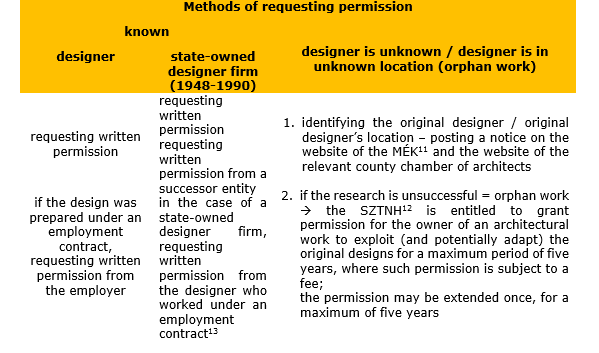

If the developer (owner) and the designer do not agree that adaptations are permitted and the period of protection has not ended, the developer (owner) will generally be required to request the designer’s permission for any alteration that qualifies as an adaptation.

We would also note that property buyers are advised to examine how the issue of adaptations was regulated, because this can give rise to disputes later.

Register of architectural copyrights

Since 1 January 2020, developers and designers have been required to deliver data pertaining to economic rights in construction documents and in buildings built on the basis of such documentation to the Register of Architectural Copyrights (“Register”).

This obligation does not apply to architectural works created before 1 January 2020, but any copyright owner can announce to the Register that they hold a copyright in a particular work or that to their knowledge another person holds a copyright in the work [voluntary declaration].

It is an important rule that the administrator of the Register publishes information pertaining to economic rights on its website and on the e-epites.hu website. The information recorded in the Register is public, and in theory it has been publicly accessible since January 2021. It is important to note, however, that according to Decree No.8/2020 (VI.26) of the Minister in Charge of the Office of the Prime Minister, the person who reports a particular piece of information is liable for the veracity and accuracy of that information, i.e. the Register cannot be relied on as an official record.

Buyers are definitely advised to check the Register in order to confirm a building’s copyright status before buying it. If you would like to know more about the Register, please click here.

Authors: András Fenyőházi and Zsanett Szabó

[1] Szeged Court of Appeals, Pf. II.20.595/2008.; BDT 2010. 2329

[2] Supreme Court, Pfv.20.303/2005/BH 2005.427

[3] See Section 1(6) of the Copyrights Act

[4] SZJSZT – 05/13, point 39

[5] Supreme Cort, Pfv.20.303/2005/BH 2005.427

[6] SZJSZT- 05/13; SZJSZT-17/15

[7] SZJSZT 1/2006

[8] SZJSZT-15/10, page 8

[1] SZJSZT 09/08/1, page 3; BDT2010. 2329

[2] István Harkai: Az átdolgozás problematikája építészeti alkotások esetében a szerzői jogban. in: Acta Univ. Sapientiae, Legal Studies 6, 6 (2017) p. 266