It is a worldwide phenomenon that due to the epidemic, the performance of a contract generally requires more time and becomes more costly. Work contracts and construction projects are specially affected by this situation. Lawyers are frequently asked these days: which party is liable and will bear the costs, if the contractor does not meet the deadline due to the virus. The answer to this question is not black and white, as it depends on several circumstances. This article addresses the most important considerations of examining late performance in the hope that it will help the readers, whether employers and contractors, to assess and optimize their position.

Establishing and recognising late performance seems a simple task. If a contractual deadline is not met, then the performance is delayed. However, if the party is unable to carry out its tasks in time due to external circumstances, for example because of force majeure events, the liability issue is no longer so obvious.

Force majeure is a complex legal definition, one might even say that it is a term used in the philosophy of law. Therefore, we have to briefly introduce the relevant principles of civil law, however our article focuses on practical everyday examples.

This article is structured around an imaginary case. First, we describe the case, then summarize the main legal points that the court may examine in a similar situation.

1. The case

The construction of an imaginary 10-storey hotel building has been affected by the Coronavirus epidemic in several ways.

Shortage of supply: During the first wave of the pandemic, the delivery of specially designed façade elements was delayed by 100 days due to a factory shutdown and border closure in Italy. Most of these building materials could not be substituted because of their unique characteristics.

Leaving the work site: Though certain works could be carried out up to the first 5 levels in the absence of these specific elements, the contractor decided to leave the work site temporarily rather than continue the construction in those parts of the building which were unaffected by the shortage. In fact, the reason behind the decision was that the company was involved in another project which was already behind schedule. Therefore, in the hope that they would be able to excuse themselves by referring to force majeure (i.e. shortage of supply caused by the virus) in case of the hotel, they restructured their resources and redirected their workers to the other project to complete it as soon as possible. After the façade elements arrived, the contractor continued the construction of the hotel, although it took a few days to get the machines and equipment up and running again.

Austerity measures: The contractor was on the verge of bankruptcy due to the pandemic. Therefore, the CFO introduced strict austerity measures, laid off several workers and sold a significant amount of the equipment.

Infections: The second wave hit the project hard again, as a viral hotspot developed at the construction site where several workers were infected, including employees who were responsible for the handling of heavy machinery. Due to the infections, the building activities had to be halted again, this time for 50 days, as the sick workers could not be replaced, and there was no spare capacity left to rely on due to the layoffs.

Obstruction by Employer: To avoid a chain reaction of delays by subcontractors carrying out successive works, the employer handed over some parts of the site to other entrepreneurs without the prior consent of the contractor. Limited access to the loading area slowed down the unloading and preparation of incoming raw materials considerably, which caused a further 15 days’ delay.

Unfortunate agreement: The parties concluded an agreement as per which the contractor agreed to transfer the designated parts of the site in order to facilitate parallel construction activities carried out by other entrepreneurs. Later on, this agreement proved to be unfortunate from the contractor’s perspective. One of its subcontractors had to be substituted due to the virus, and the new subcontractor was unable carry out the works with its oversize equipment within the reduced area. This induced serious allocation problems and led to a further 70 days’ delay.

Claim: Finally, the Contractor completed the works with a 260-day delay, therefore the employer demanded liquidated damages for 200 days and compensation for loss of profit for the 60 days by which the opening of the hotels had to be postponed.

2. How to calculate the amount of contractual delay penalty and damages for late performance

Knowing the facts of the case, surely the readers have their own impression of a just solution. Still they might disagree on several points depending on whether they are employers or contractors. Let’s see what are the main legal considerations that the court would probably examine if the parties took the case before court.

The main principle is that the contractual penalty is payable for the entire period of the delay, for example, for each day elapsed since the contractual deadline until the actual completion of the works. However, the contractor is not required to pay penalty for those days when the construction activities were prevented by force majeure events or by the principal (employer) itself.

The judicial practice recognizes the following legal bases for excuse:

Obstacles: The contractor is not liable for the delay caused by obstacles which were (i) beyond its control, (ii) unforeseeable at the conclusion of the contract and (iii) unavoidable even by reasonable diligence.

Beyond control: An event is considered to have occurred beyond the contractors’ control, if it cannot be prevented either by the contractor itself, or by any possible human intervention. These could be, for example, the following events: natural disasters, like earthquake, fire etc.; and certain consequences of an epidemic; certain politico-social events, such as war, uprising, closure of a transport route (airport); state measures: import/export bans, currency restrictions, embargoes, boycotts, closure of borders or regions or municipalities. However, contractors cannot excuse a breach (e.g. delay) caused by deficiencies in their own skills and capacities to perform. In their defence they cannot generally rely on problems of supply or on the behaviour of employees and subcontractors.

Unforeseeability: Furthermore, contractors cannot successfully refer to circumstances which could be regarded as highly unlikely, but still possible adverse scenarios. For example, referring to weather conditions such as days rainier or colder than the average, may not be sufficient for exemption as opposed to severe or extraordinary weather (e.g. tornado, torrential rainfall). Contractors generally can be exempted from liability when the given event could not have been expected even as a worth-case scenario by a professional businessman acting with due care and diligence.

Unavoidability: Likewise, as long as the necessary materials can be collected from an alternative supplier or by using an alternative route, difficulty in obtaining raw materials may not be a legitimate argument, even if the original supply chain is completely unavailable. It is important to note that contractors have to show proper care to avoid any impediment and / or mitigate their consequences. Therefore, the contractor must not wait until the originally planned way of supply reopens, but must look for a substitute supplier. However, if the contractor selects the alternative supplier in line with the interest of its customer, the contractor cannot be held liable for the extra time required for arranging the change of source of supply.

Employer’s negligence: Also contractors are not liable for delay caused by the employer. If the employer fails to fulfil its tasks necessary for carrying out construction activities, the contractor’s liability is excluded. A typical example of this is when the employer does not or cannot provide adequate physical or legal access to the site. For instance, there is no proper access to the construction staging area or the ownership of the construction site is disputed or a declaration / permit necessary for the construction is missing due to the employer’s default. Similarly, any delay is attributable to the employer when the contractor is prevented from using the site by third parties acting on behalf of the employer, or by events that fall within the employer’s scope of risks and responsibilities, such as obstacles by other contractors, archaeological excavations, infrastructural deficit, etc.

Extra request: Furthermore, the contractor cannot be blamed for the delay caused by changes proposed by the employer (e.g. extra works in addition to the original technical content).

As the above examples show, there are strict requirements for excusing delay. Employers only need to present evidence that the contractual deadline is missed, whereas the contractor has to prove (i) the causes of excuses (e.g. obstacles, employer’ negligence, extra requests, etc.) in detail, (ii) the fact that these events unavoidably hindered construction, and that (iii) the period of delay was directly caused by them.

The contractors also have to present evidence of how the different causes for delay are related in time and whether they were crucial to the project or not. If several adverse events occur at the same time, their effects cannot be added up. For example, if the employer’s negligence (e.g. failure to provide proper access to the site) and an obstacle (e.g. flood) prevent the building activities within the same period (e.g. in the first two weeks of the construction), their effects cannot be counted cumulatively (i.e 2+2 weeks), and they can be taken into consideration only once.

Furthermore, If the given obstacles were not crucial to the performance of the tasks, in other words they could have been avoided or their effects could have been reduced (e.g. by reasonable work reorganisation or by involving further manpower and resources), they may be taken into account, but only to the extent that such obstacles could not have been eliminated. For illustration, if a prolonged shortage of an energy supply hinders certain works, while it does not affect others, the contractor must revise its time schedule and show reasonable efforts to carry out the unaffected works even if they were planned to be completed at a later stage of the project. Failing to rationalize the timing, and waiting for the problem to be solved, is never a proper tactic, not even if the construction activities were hindered by the employer. In principle, contractors can excuse themselves only for those days that would have been delayed even if they had used their best endeavour to reorganize the works.

These are the factors that should be covered and considered carefully by detailed forensic expert reports. The courts apply strict standards when evaluating expert opinions. It is not sufficient to state in general terms whether the delay should be considered to be excused or not. The causes and the effects of delays must be illustrated in the light of the whole construction program and the sequence in which they occur and must be compared to alternative scenarios (e.g. possible work reorganisations etc.). In most cases detailed time charts and variable time schedules must be presented highlighting how the impediments affected the construction.

3. Solution to the case

In our case study, the employer initiates a claim against the contractor demanding contractual penalty for 200 days and compensation for loss of profit for 60 days. The contractor refers to several force majeure events in its statement of defence, such as shortage of supply, infections, and obstruction by the employer. Let’s see how the court would probably assess these circumstances:

Shortage of supply: As regards the special façade elements, in our imaginary case the expert confirms the contractor’s position that these building materials could not be substituted because of their unique characteristics. Therefore, the court probably would accept the argument that factory shutdown and border closure in Italy were beyond the control of the contractor (and its subcontractor). Thus, the contractor cannot be held liable for shortage and delay in materials supply. However, our fictional expert points out that the contractor failed to carry out the necessary measures to reduce the extent of the delay. He argues that, if the contractor had reorganised the project properly and continued the construction with the fit-out works on the first 5 floor, which were not affected by the shortage of material, it could have saved 25 days. Furthermore, the contractor caused a further 5 days’ delay by leaving the work site temporarily. When it resumed work, the re-establishing of its infrastructure led to loss of time and efficiency. In his defence, the contractor could refer to the original time schedule, which laid down that the fit-out works were planned to commence after the installation of all façade elements. But the court would probably reject this argument, since contractors are expected to make reasonable efforts to reorganize their time schedule if necessary to reduce delay. If the expert establishes that it would not have been unreasonably burdensome to continue with fit-out works in order to save time, the contractor cannot be released for this omission. In this case the court is likely to hold the contractor liable for 30 days out of 100.

Labour shortages: The court would probably adopt a tough stance on the delay arising from the COVID infections. Although the pandemic was not unforeseeable at the time of concluding the contract, in most cases, illnesses and in particular labour shortages are not considered to have occurred outside the contractor’s control. As a general rule, contractors cannot excuse delay caused by deficiencies in their own skills and capacities to perform. Courts tend to dismiss such defence even in case of natural persons, let alone companies that are subject to stricter assessment in this respect. This is especially true when the performer weakens its own ability to perform, as it happened in this case, where sick workers could not be replaced, because there was no spare capacity left to rely on due to the austerity measures. Therefore, regarding the labour shortages, the court is likely to hold liable the contractor for all 50 days out of 50.

Obstruction by employer: Our fictitious employer does not dispute the fact that it handed over certain areas of contractor’s work site to other entrepreneurs without the contractor’s prior consent. The court would probably acknowledge the employer’s right to take the necessary measures to mitigate damages in order to avoid a chain reaction of delays and to engage further contractors at the contractor’s cost. At the same time employers in this situation are still obliged to fulfil their main obligations, namely to provide workspace and to coordinate the works of their various subcontractors. Thus, the court is unlikely to hold liable the contractor for 40 days’ delay resulting from the employer’s failure to comply with these obligations.

Problems after the interim agreement concerning the site: In our case both parties acknowledge the fact that they modified the contract to facilitate parallel working by handing over certain sites to other contractors. However, the parties probably would take a different position on the legal consequences of their agreement. The contractor would argue that the employer takes advantage of its cooperative attitude when it insists on enforcing the provisions of this interim agreement in circumstances that were entirely different from the original scenario. The purpose of the modification was to transfer those parts of the site that were not essential for the contractor’s work in order to speed up the completion of the project without hindering its activities. But the situation changed significantly when the contractor’s original subcontractors had to be substituted due to the virus. It became obvious that the new subcontractor would be unable to carry out the works with its oversize equipment within the reduced area. The employer could refute the contractor’s argument by emphasizing that the contractor should have considered more carefully which parts of the site could be transferred, but it had no right to modify their agreement unilaterally and subsequently.

The court would probably find in favour of the employer on this issue and point out that at the conclusion of a contract, both parties must consider the risk that there may be adverse changes in the circumstances of their performance. The same principle applies to the modification of contracts. The parties must also take into account those risks that are foreseeable at the time of the modification in addition to those predictable at the conclusion of the original contract. Most probably our expert will establish that that the reduced area for work was so narrow that the original subcontractor was essentially the only one capable of carrying out the work there. The contractor should have considered the risk of being unable to replace the original foreign subcontractor with another contractor if this should be necessary – as it happened due to the coronavirus restrictions, which was a predictable scenario at the time of the modification. Even though the risks stemming from the epidemic could not have been known at the time of the conclusion of the original contract, the parties must have been aware of them when it was later amended. Therefore, considering the allocation problems on the site after the modification of the contract, the court is likely to hold the contractor liable for all 70 days out of 70.

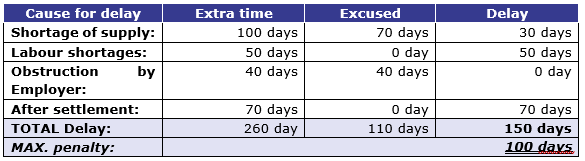

Ruling on the contractual penalty: By definition, contractual penalty claims do not require evidence of whether any damage has actually occurred nor do they have to quantify the extent of the damage. Thus, the employer has to prove only the number of days elapsed after the deadline, which is 260 days in our example. The penalty has to be paid for this period except those days for which the contractor successfully excused himself. In this case the contractor is released from liability for 110 days out of 260, thus the calculation is based on the remaining (260-110=) 150 days. However, according to the Contract, the contractual penalty for late performance is 0,3% per day up to maximum 30% of the fee. This means that the penalty is capped at (30 / 0,3=) 100 days. Therefore, the Employer is entitled to an amount equalling its fee X 0,3 X 100 for late performance.

Considering liability for damages: Employers have a right to claim compensation for damages arising from the delay beyond the amount of the contractual penalty, however the benefit of the burden of proof mentioned above, does not apply in this respect. They have to prove and quantify the exact amount of the damages suffered. For example, if our fictitious employer (the Hotel owner) cannot prove that it would have been able to generate a higher amount of revenue than the amount of the contractual penalty if the Hotel had opened earlier, it cannot claim any further damages. It is important to note that those damages may be claimed that emerged beyond the amount of the penalty.

Possible reduction of the amount of contractual penalty: As explained above, the main rule is that employers are not obliged to prove the damages they suffered in order to be able to claim contractual penalty. However, in certain cases courts can be successfully requested to reduce the amount of the penalty. For example, if the employer suffered no significant damages due to breach of contract, the court may reduce the amount of the penalty if it is fully and absolutely obvious that the amount claimed is significantly disproportionate compared to the losses caused by the delay. Furthermore, the court may also reduce the amount of the penalty in case of gross disparity between the value of the service and the amount of the liquidated damages.

4. Recommendations

For successful claim enforcement, employers are recommended to take the following steps:

They should inform their contractors about the possible consequences of a delay when concluding the contract. Consequential damages can only be claimed up to the extent the contractor was able to foresee the damages as possible consequence of a delay at the time of the conclusion of the contract.

If they are temporarily unable to provide proper access to the site, they should inform the contractor without delay and cooperate in reorganising the works.

If different contractors hinder each other’s work on the site, employers must cooperate with the contractors and reschedule the works in such a way that the coordinated workflow can be restored as soon as possible.

To fulfil their obligation to mitigate damages arising from the delay, in certain cases, it may be beneficial for employers to involve further manpower and resources at the contractor’s cost to facilitate the completion of the project.

They should document precisely the consequences of the delay caused by the contractor, e.g. extra costs incurred by involving further resources, lost revenue etc,

For sufficient excuse of delay, contractors are recommended to take the following steps:

They should collect detailed evidence of obstacles, employer’s negligence and of changes causing the delay. (See point 2.)

They should illustrate how the different causes of delay are related in time and whether they were crucial to the project or not. If several adverse events occur at the same time, their effects cannot be added up.

They should highlight why the given obstacles were critical to the implementation of tasks. (Remember, if they could have been avoided or their effects could have been reduced, e.g. by reasonable work reorganisation or by involving further manpower and resources, they may be taken into account, but only to the extent that such obstacles could not have been eliminated.)

They should show proper care to avoid any obstacle and / or mitigate their consequences even if it is caused by the employer. It is advisable to describe what kind of measures, reorganisations, involvement of further resources was considered and implemented in order to avoid / mitigate damages.

If a given obstacle hinders certain works, while it does not affect others, the contractor should revise their time schedule and show reasonable efforts to carry out the unaffected works even if they were planned to be completed at a later stage of the project.

The causes of delay and their effects must be illustrated in the light of the whole construction program and the sequence in which such delays occur, and must even be compared to alternative scenarios using time schedules. This is most commonly done through the so called critical path method.

Author: Bence Rajkai